Recent media coverage of Dr. Sergio Canavero’s plans to perform the world’s first full-body transplant has attracted both admiration and repulsion.

The Canadian connection—a young graduate of Trinity Western University—makes the story even more intriguing. William Sikkema, who is currently completing a Ph.D. at Rice University in Texas, has created Texas-PEG, a nanomaterial that has shown great potential for repairing spinal cord injuries. He explained the science behind it to CBC’s Quirks and Quarks recently.

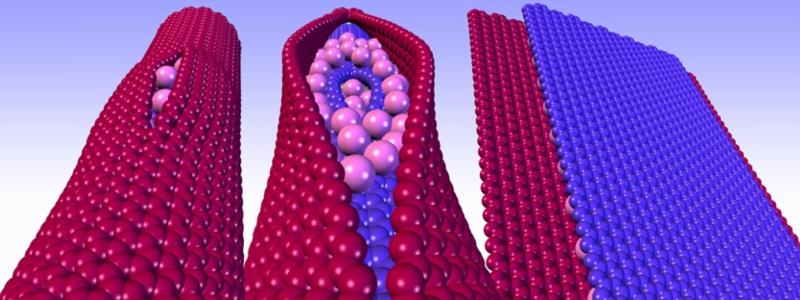

Canavero hopes to take Texas-PEG, a functionalized type of graphene nanoribbons, a step further and use it for his upcoming body transplant procedure.

Sikkema has said that in his opinion, the controversial procedure is more sensationalism than science. He also notes that breaking new ground is par for the course in his field, and that a few decades ago, people had similar negative feelings about heart transplants and blood transfusions.

“I am conflicted. I’m not sure exactly where I stand,” he told the National Post. “Sergio is going to do it, regardless of what I do, or what I give him. But I can make it safer. I can lower the risk.”

For Sikkema, lowering the risk fits with his personal goal as a scientist to do good. He’s also working on an artificial retina that he hopes will help blind people see, for example.

For Dr. Eve Stringham, TWU’s vice-provost, research and graduate studies, as well as one of Sikkema’s former biology professors, there are other ethical questions to consider.

The first is the question of identity. “What is personhood?” asks Stringham. “Will the head recognize the body as self? Recent history with face transplants and limb transplants have highlighted some of the psychological risks.”

A head/body transplant would also raise questions related to offspring. Would the patient’s offspring belong to him or her, or to the donor body? “This raises questions regarding consent, custody, rights of the family of the ‘donor body’ to visit offspring, legal obligations of the ‘body’s’ estate, and more,” says Stringham.

There are also other risks to consider. “If the recipient’s death is imminent, then the transplant may seem to be worth the risk. But, for the person whose body is deteriorating slowly, at what point would it be ethically correct to do the transplant? What if it ends up shortening their lifespan? Additionally, is it ethical for an entire body to be used for such a risky procedure when the different organs could save the lives of so many other people?”

The procedure also poses some danger to animals given the need for pre-clinical animal testing. “Animal care committees consider only proposals that have been shown to have real scientific merit first,” explains Stringham. “Then they look to minimize animal use and suffering. You try to replace the use of animals with alternative techniques, reduce the number of animals used to obtain information, and refine the way experiments are carried out to make sure animals don’t suffer.”

To interview Dr. Eve Stringham about this matter, contact media@twu.ca.